- Management API

- Catalogs, Datasets, and Offers

- EDC Entities

- Catalog Generation

- Contract Negotiations

- Transfer Processes

The control plane is responsible for assembling catalogs, creating contract agreements that grant access to data, managing data transfers, and monitoring usage policy compliance. Control plane operations are performed by interacting with the Management API. Consumer and provider control planes communicate using the Dataspace Protocol (DSP). This section provides an overview of how the control plane works and its key concepts.

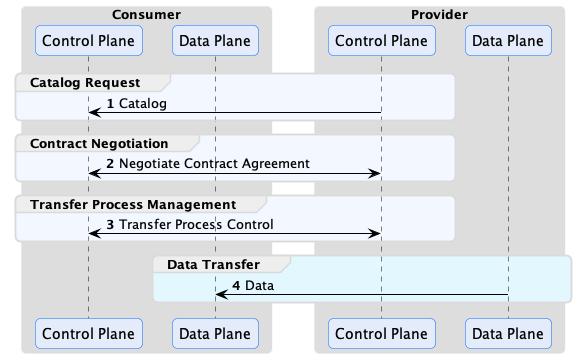

The main control plane operations are depicted below:

The consumer control plane requests catalogs containing data offers, which are then used to negotiate contract agreements. A contract agreement is an artifact that acts as a token granting access to a data set. It encodes a set of usage policies (as ODRL) and is bound to the consumer via its Participant ID. Every control plane must be configured with a Participant ID, which is the unique identifier of the dataspace participant operating it. The exact type of identifier is dataspace-specific but will often be a Web DID if the Decentralized Claims Protocol (DCP) is used as the identity system.

After obtaining a contract agreement, the consumer can initiate a data transfer. A data transfer controls the flow of data, but it does not send it. That task is performed by the consumer and provider data planes using a separate wire protocol. Data planes are typically specialized technology, such as a messaging system or data integration platform, deployed separately from the control plane. A control plane may use multiple data planes and communicate with them via a RESTful interface called the Data Plane Signaling API.

EDC is designed to handle all general forms of data. It’s important to note that a data transfer does not need to be file-based. It can be a stream, such as a market feed or an API that a client queries. Moreover, a data transfer does not need to be completed. It can exist indefinitely and be paused and resumed by the control plane at intervals. Now, let’s jump into the specifics of how the control plane works, starting briefly with the Management API and proceeding to catalogs.

Management API

The Management API is a RESTful interface for client applications to interact with the control plane. All client operations described in this section use the Management API. We won’t cover the API in detail here since there is an OpenAPI definition. The API can be secured using an authentication key or third-party OAuth2 identity provider, but it is important to note that it should never be exposed over the Internet or other non-trusted networks.

The openapi documentation is available following this link: https://eclipse-edc.github.io/Connector/openapi/management-api/

Catalogs, Datasets, and Offers

A data provider uses its control plane to publish a data catalog that other dataspace participants access. Catalog requests are made using DSP (HTTP POST). The control plane will return a response containing a DCAT Catalog The following is an example response with some sections omitted for brevity:

{

"@context": {...},

"dspace:participantId": "did:web:example.com",

"@id": "567bf428-81d0-442b-bdc8-437ed46592c9",

"@type": "dcat:Catalog",

"dcat:dataset": [

{

"@id": "asset-1",

"@type": "dcat:Dataset",

"description": "...",

"odrl:hasPolicy": {...},

"dcat:distribution": [{...}]

}

]

}

Catalogs contain Datasets, which represent data the provider wishes to make available to the requesting client. A Dataset has two important properties: odrl:hasPolicy, which is an ODRL usage policy, and one or more dcat:distribution entries that describe how to obtain the data. The catalog is serialized as JSON-LD. It is highly recommended that you become familiar with JSON-LD, and in particular, the JSON-LD Playground, since EDC makes heavy use of it.

Why does EDC use JSON-LD instead of plain JSON? There are two reasons. First, DSP is based on DCAT and ODRL, which rely on JSON-LD. As you will see, many EDC entities can be extended with custom attributes added by end-users. EDC needed a way to avoid property name clashes. JSON-LD provides the closest thing to a namespace feature for plain JSON.

Catalogs are not static documents. When a data consumer requests a catalog from a provider, the provider’s control plane dynamically generates a response based on the consumer’s identity and credentials. For example, a provider may offer specific datasets to a consumer or category of consumer (for example, if it is a tier-1 or tier-2 partner).

You will learn more about restricting access to datasets in the next section, but one way to do so is through the offer associated with a dataset. The following odrl:hasPolicy contains an Offer that specifies a dataset can only be used by an accredited manufacturer:

"odrl:hasPolicy": {

"@id": "...",

"@type": "odrl:Offer",

"odrl:obligation": {

"odrl:action": {

"@id": "use"

},

"odrl:constraint": {

"odrl:leftOperand": {

"@id": "ManufacturerAccredidation"

},

"odrl:operator": {

"@id": "odrl:eq"

},

"odrl:rightOperand": "active"

}

}

},

An offer defines usage policy. Usage policies are the requirements and permissions - or, more precisely, the duties, rights, and obligations - a provider imposes on a consumer to grant access to data. In the example above, the provider requires the consumer to be an accredited manufacturer. In practice, policies translate down into checks and verifications at runtime. When a consumer issues a catalog request, it will supply its identity (e.g., a Web DID) and potentially a set of Verifiable Presentations (VP). The provider control plane could check for a valid VP, or perform a back-office system lookup based on the client identity. Assuming the check passes, the dataset will be included in the catalog response.

A dataset will also be associated with one or more dcat:distributions:

"dcat:distribution": [

{

"@type": "dcat:Distribution",

"dct:format": {

"@id": "HttpData-PULL"

},

"dcat:accessService": {

"@id": "a6c7f3a3-8340-41a7-8154-95c6b5585532",

"@type": "dcat:DataService",

"dcat:endpointDescription": "dspace:connector",

"dcat:endpointUrl": "http://localhost:8192/api/dsp",

"dct:terms": "dspace:connector",

"dct:endpointUrl": "http://localhost:8192/api/dsp"

}

},

{

"@type": "dcat:Distribution",

"dct:format": {

"@id": "S3-PUSH"

},

"dcat:accessService": {

"@id": "a6c7f3a3-8340-41a7-8154-95c6b5585532",

"@type": "dcat:DataService",

"dcat:endpointDescription": "dspace:connector",

"dcat:endpointUrl": "http://localhost:8192/api/dsp",

"dct:terms": "dspace:connector",

"dct:endpointUrl": "http://localhost:8192/api/dsp"

}

}

]

A distribution describes the wire protocol a dataset is available over. In the above example, the dataset is available using HTTP Pull and S3 Push protocols (specified by the dct:format property). You will learn more about the differences between these protocols later. A distribution will be associated with a dcat:accessService, which is the endpoint where a contract granting access can be negotiated.

If you would like to understand the structure of DSP messages in more depth, we recommend looking at the JSON schemas and examples provided by the Dataspace Protocol Specification (DSP).

EDC Entities

So far, we have examined catalogs, datasets, and offers from the perspective of DSP messages. We will now shift focus to the primary EDC entities used to create them. EDC entities do not have a one-to-one correspondence with DSP concepts, and the reason for this will become apparent as we proceed.

Assets

An Asset is the primary building block for data sharing. An asset represents any data that can be shared. An asset is not limited to a single file or group of files. An asset could be a continual stream of data or an API endpoint. An asset does not even have to be physical data. It could be a set of computations performed at a later date. Assets are data descriptors loaded into EDC via its Management API (more on that later). Notice the emphasis on “descriptors”: assets are not the actual data to be shared but describe the data. The following excerpt shows an asset:

{

"@context": {

"edc": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/"

},

"@id": "899d1ad0-532a-47e8-2245-1aa3b2a4eac6",

"properties": {

"somePublicProp": "a very interesting value"

},

"privateProperties": {

"secretKey": "..."

},

"dataAddress": {

"type": "HttpData",

"baseUrl": "http://localhost:8080/test"

}

}

When a client requests a catalog, the control plane processes its asset entries to create datasets in a DSP catalog. An asset must have a globally unique ID. We strongly recommend using the JDK UUID implementation. Entries under the properties attribute will be used to populate dataset properties. The properties attribute is open-ended and can be used to add custom fields to datasets. Note that several well-known

properties are included in the edc namespace: id, description, version, name, contenttype (more on this in the next section on asset expansion).

In contrast, the privateProperties attribute contains properties that are not visible to clients (i.e., they will not be serialized in DSP messages). They can be used to internally tag and categorize assets. As you will see, tags are useful to select groups of assets in a query.

Why is the term

Assetused and notDataset? This is mostly for historical reasons since the EDC was originally designed before the writing of the DSP specification. However, it was decided to keep the two distinct since it provides a level of decoupling between the DSP and internal layers of EDC.

Remember that assets are just descriptors - they do not contain actual data. How does EDC know where the actual data is stored? The dataAddress object acts as a pointer to where the actual data resides. The DataAddress type is open-ended. It could point to an HTTP address (HttpDataAddress), S3 bucket (S3DataAddress), messaging topic, or some other form of storage. EDC supports a defined set of storage types. These can be extended to include support for virtually any custom storage. While data addresses can contain custom data, it’s important not to include secrets since data addresses are persisted. Instead, use a secure store for secrets and include a reference to it in the DataAddress.

Understanding Expanded Assets

The @context property on an asset indicates that it is a JSON-LD type. JSON-LD (more precisely, JSON-LD terms) is used by EDC to enable namespaces for custom properties. The following excerpt shows an asset with a custom property, dataFeed:

{

"@context": {

"edc": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/",

"market-systems": "http://w3id.org/market-systems/v0.0.1/ns/"

},

"@id": "...",

"properties": {

"dataFeed": {

"feedName": "Market Data",

"feedType": "PRICING",

"feedFrequency": "DAILY"

}

}

}

Notice a reference to the market-systems context has been added to @context in the above example. This context defines the terms dataFeed, feedName, feedType, and feedFrequency. When the asset is added to the control plane via the EDC’s Management API, it is expanded according to the JSON expansion algorithm This is essentially a process of inlining the full term URIs into the JSON structure. The resulting JSON will look like this:

{

"@id": "...",

"https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/properties": [

{

"http://w3id.org/market-systems/v0.0.1/ns/dataFeed": [

{

"http://w3id.org/market-systems/v0.0.1/ns/feedName": [

{

"@value": "Market Data"

}

],

"http://w3id.org/market-systems/v0.0.1/ns/feedType": [

{

"@value": "PRICING"

}

],

"http://w3id.org/market-systems/v0.0.1/ns/feedFrequency": [

{

"@value": "DAILY"

}

]

}

]

}

]

}

Be careful when defining custom properties. If you forget to include a custom context and use simple property names (i.e., names that are not prefixed or a URI), they will be expanded using the EDC default context,

https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/.

EDC persists the asset in expanded form. As will be shown later, queries for assets must reference property names in their expanded form.

Policies and Policy Definitions

Policies are a generic way of defining a set of duties, rights, or obligations. EDC and DSP express policies with ODRL. EDC uses policies for the following:

- As a dataset offer in a catalog to define the requirements to access data

- As a contract agreement that grants access to data

- To enable access control

Policies are loaded into EDC via the Management API using a policy definition, which contains an ODRL policy type:

{

"@context": {

"edc": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/"

},

"@type": "PolicyDefinition",

"policy": {

"@context": "http://www.w3.org/ns/odrl.jsonld",

"@id": "8c2ff88a-74bf-41dd-9b35-9587a3b95adf",

"duty": [

{

"target": "http://example.com/asset:12345",

"action": "use",

"constraint": {

"leftOperand": "headquarter_location",

"operator": "eq",

"rightOperand": "EU"

}

}

]

}

}

A policy definition allows the policy to be referenced by its @id when specifying the usage requirements for a set of assets or access control. Decoupling policies in this way allows for a great deal of flexibility. For example, specialists can create a set of corporate policies that are reused across an organization.

Contract Definitions

Contract definitions link assets and policies by declaring which policies apply to a set of assets. Contract definitions contain two types of policy:

- Contract policy

- Access policy

Contract policy determines what requirements a data consumer must fulfill and what rights it has for an asset. Contract policy corresponds directly to a dataset offer. In the previous example, a contract policy is used to require a consumer to be an accredited manufacturer. Access policy determines whether a data consumer can access an asset. For example, if a data consumer is a valid partner. The difference between contract and access policy is visibility: contract policy is communicated to a consumer via a dataset offer in a catalog, while access policy remains “hidden” and is only evaluated by the data provider’s runtime.

Now, let’s examine a contract definition:

{

"@context": {

"edc": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/"

},

"@type": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/ContractDefinition",

"@id": "test-id",

"edc:accessPolicyId": "access-policy-1234",

"edc:contractPolicyId": "contract-policy-5678",

"edc:assetsSelector": [

{

"@type": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/Criterion",

"edc:operandLeft": "id",

"edc:operator": "in",

"edc:operandRight": ["id1", "id2", "id3"]

},

{

"@type": "https://w3id.org/edc/v0.0.1/ns/Criterion",

"edc:operandLeft": "productCategory",

"edc:operator": "=",

"edc:operandRight": "gold"

},

]

}

The accessPolicyId and contractPolicyId properties refer to policy definitions. The assetsSelector property is a query (similar to a SQL SELECT statement) that returns a set of assets the contract definition applies to. This allows users to associate policies with specific assets or types of assets.

Since assetsSelectors are late-bound and evaluated at runtime, contract definitions can be created before assets exist. This is a particularly important feature since it allows data security to be put in place prior to loading a set of assets. It also enables existing policies to be applied to new assets.

Catalog Generation

We’re now in a position to understand how catalog generation in EDC works. When a data consumer requests a catalog from a provider, the latter will return a catalog result with datasets that the former can access. Catalogs are specific to the consumer and dynamically generated at runtime based on client credentials.

When a data consumer makes a catalog request via DSP, it will send an access token that provides access to the consumer’s verifiable credentials in the form of a verifiable presentation (VP). We won’t go into the mechanics of how the provider obtains a VP - that is covered by DCP and the EDC IdentityHub. When the provider receives the request, it generates a catalog containing datasets using the following steps:

The control plane first retrieves contract definitions and evaluates their access and contract policies against the consumer’s set of claims. These claims are populated from the consumer’s verifiable credentials and any additional data provided by custom EDC extensions. A custom EDC extension could look up claims such as partner tier in a back-office system. Next, the assetsSelector queries from each passing contract definition is then evaluated to return a list of assets. These assets are iterated, and a dataset is created by combining the asset with the contract policy specified by the contract definition. The datasets are then collected into a catalog and returned by the client. Note that a single asset may result in multiple datasets if more than one contract definition selects it.

Designing for Optimal Catalog Performance

Careful consideration needs to be taken when designing contract definitions, particularly the level of granularity at which they operate. When a catalog request is made, The access and contract policies of all contract definitions are evaluated, and the passing ones are selected. The asset selector queries are then run from the resulting set. To optimize catalog generation, contract definitions should select groups of assets rather than correspond in a 1:1 relationship with an asset. In other words, limit contract definitions to a reasonable number and use them as a mechanism to filter groups of assets. Adding custom asset properties that serve as selection labels is an easy way to do this.

Contract Negotiations

Once a consumer has received a catalog, it can request access to a dataset by sending a DSP contract negotiation request using the Management API. The contract negotiation takes the dataset offer as a parameter. When the request is received, the provider will respond with an acknowledgment. Contract negotiations are asynchronous, which means they are not completed immediately but sometime in the future. A contract negotiation progresses through a series of states defined by the DSP specification (which we will not cover). Both the consumer and provider can transition the negotiation. When a transition is attempted, the initiating control plane sends a DSP message to the counterparty.

If a negotiation is successfully completed (termed finalized), a DSP contract agreement message is sent to the consumer. The message contains a contract agreement that can be used to access data by opening a transfer process:

{

"@context": "https://w3id.org/dspace/2024/1/context.json",

"@type": "dspace:ContractAgreementMessage",

"dspace:providerPid": "urn:uuid:a343fcbf-99fc-4ce8-8e9b-148c97605aab",

"dspace:consumerPid": "urn:uuid:32541fe6-c580-409e-85a8-8a9a32fbe833",

"dspace:agreement": {

"@id": "urn:uuid:e8dc8655-44c2-46ef-b701-4cffdc2faa44",

"@type": "odrl:Agreement",

"odrl:target": "urn:uuid:3dd1add4-4d2d-569e-d634-8394a8836d23",

"dspace:timestamp": "2023-01-01T01:00:00Z",

"odrl:permission": [{

"odrl:action": "odrl:use" ,

"odrl:constraint": [{

"odrl:leftOperand": "odrl:dateTime",

"odrl:operand": "odrl:lteq",

"odrl:rightOperand": { "@value": "2023-12-31T06:00Z", "@type": "xsd:dateTime" }

}]

}]

},

"dspace:callbackAddress": "https://example.com/callback"

}

EDC implements DSP message exchanges using a reliable quality of service. That is, all message operations and state machine transitions are performed reliably in a transaction context. EDC will only commit a state machine transition if a message is successfully acknowledged by the counterparty. If a send operation fails, the associated transition will be rolled back, and the message will be resent. As with all reliable messaging systems, EDC operations are idempotent.

Working with Asynchronous Messaging and Events

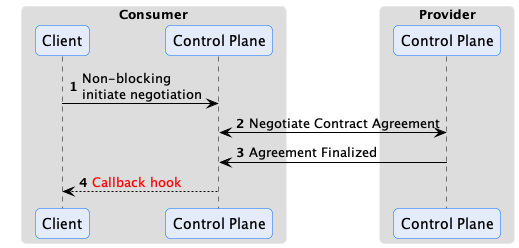

DSP and EDC are based on asynchronous messaging, and it is important to understand that and design your systems appropriately. One anti-pattern is to try to “simplify” EDC by creating a synchronous API that wraps the underlying messaging and blocks clients until a contract negotiation is complete. Put simply, don’t do that, as it will result in complex, inefficient, and incorrect code that will break EDC’s reliability guarantees. The correct way to interact with EDC and the control plane is expressed in the following sequence diagram:

EDC has an eventing system that code can plug into and receive events when something happens via a callback hook. For example, a contract negotiation is finalized. The EventRouter is used by extension code to subscribe to events. Two dispatch modes are supported: asynchronous notification or synchronous transactional notification. The latter mode can be used to reliably deliver the event to an external destination such as a message queue, database, or remote endpoint. Integrations will often take advantage of this feature by dispatching contract negotiation finalized events to another system that initiates a data transfer.

Reliable Messaging

EDC implements reliable messaging for all interactions, so it is important to understand how this quality of service works. First, all messages have a unique ID and are idempotent. If a particular message is not acknowledged, it will be resent. Therefore, it is expected the receiving endpoint will perform de-duplication (which all EDC components do). Second, reliable messaging works across restarts. For example, if a runtime crashes before it can send a response, the response will be sent either by another instance (if running in a cluster) or by the runtime when it comes back online. Reliability is achieved by recording the state of all interactions using state machines to a transactional store such as Postgres. State transitions are initiated in the context of a transaction by sending a message to the counterparty, which is only committed after an acknowledgment is received.

Transfer Processes

After a Contract Negotiation has been finalized, a consumer can request data associated with an asset by initiating a Transfer Process via the Management API.

A finite transfer process completes after the data, such as a file, has been transferred. Other types of data transfers, such as a data stream or access to an API endpoint, may be ongoing. These types of transfer processes are termed non-finite because there is no specified completion point. They continue until they are explicitly terminated or canceled.

Pay careful attention to how data is modeled. In particular, model your assets in a way that minimizes the number of Contract Negotiations and Transfer Processes that need to be created. For large data sets such as machine-learning data, this is relatively straightforward: an asset can represent individual data set. Consumers will typically need to transfer the data once or infrequently, so the number of Contract Negotiations and Transfer Processes will remain small, typically one Contract Negotiation and a few transfers.

Now, let’s take as an example a supplier that wishes to expose parts data to their partners. Do not model each part as a separate asset, as that would require at least one contract negotiation and transfer process per part. If there are millions of parts, the number of contract negotiations and transfer processes will quickly grow out of control. Instead, having a single asset represents aggregate data, such as all parts, or a significant subset, such as a part type. Only one Contract Negotiation will be needed, and if the Transfer Process is non-finite and kept open, consumers can make multiple parts data requests (over the course of hours, days, months, etc.) without incurring additional overhead.

Flow Types

We’ll explain how to open a Transfer Process in the next section. First, it is important to understand the two modes for sending data from a provider to a consumer that EDC supports.

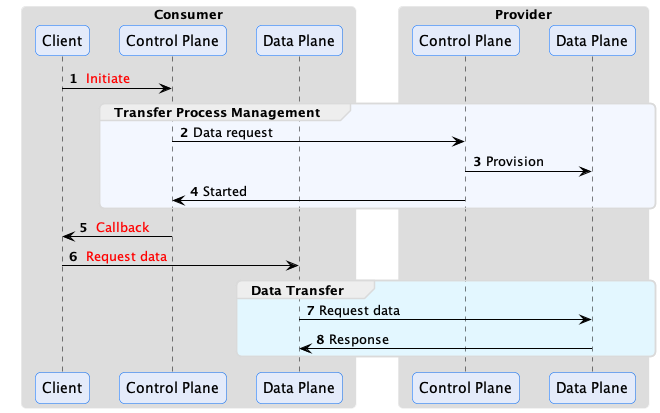

Consumer Pull

It requires the consumer to initiate the data flow operation. A common example of this is when a consumer makes an HTTP request to an endpoint and receives a response or pulls a message off a queue:

The EDR (Endpoint Data Reference) contains all the coordinates to reach the provider public endpoint where the data can be fetched. In the basic case, it is an HTTP endpoint, but it could be a message broker, an object storage and so on.

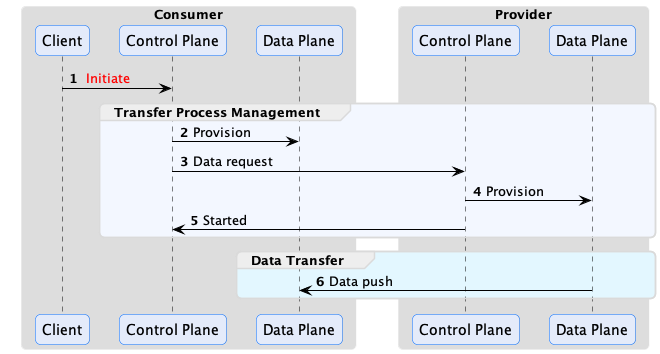

Provider Push

It requires the provider to actively push data to the consumer.

Note that, on the consumer side, the data plane role is to prepare the destination endpoint.

An example of provider push is when a consumer wishes to receive a dataset at an object storage endpoint that it controls.

Since the provider may need time to prepare the data, the consumer sends an access token when initiating a Transfer Process. The provider uses this token to push the data once it is ready.

Transfer Process States

Now that we have covered how transfer processes work at a high level, let’s look at the specifics. A transfer process is a shared state machine between the consumer and provider control planes. A transfer process will transition between states in response to a message received from the counterparty or as the result of a Management API operation. For example, a consumer will create a transfer process request via its Management API and send a request message to the provider. If the provider acknowledges the request with an OK, the transfer process state machine will be set to the REQUESTED state on both the consumer and provider. When the provider control plane is ready, it will send a message to the consumer, and the state machine will be transitioned to STARTED on both control planes.

The following are the most important transfer process states:

- REQUESTED - The consumer has requested a data transfer from the provider.

- STARTED - The consumer has received a start message from the provider. The data is available and can be pulled by the consumer or will be pushed by the provider.

- SUSPENDED - The consumer or provider has received a suspend message from the counterparty. All in-process data send operations will be paused.

- RESUMED - The consumer or provider has received a resume message from the counterparty. All in-process data send operations will be restarted.

- COMPLETED - The data transfer has been completed.

- TERMINATED - The consumer or provider has received a termination message from the counterparty. All in-process data send operations will be stopped.

There are a number of internal states that the consumer or provider can transition into without notifying the other party. The two most important are:

- PROVISIONED - When a data transfer request is made through the Management API on the consumer, its state machine will first transition to the PROVISIONED state to perform any required setup. After this is completed, the consumer control plane will dispatch a request to the provider and transition to the REQUESTED state. The state machine on the provider will transition to the PROVISIONED state after receiving a request and asynchronously completing any required data pre-processing.

- DEPROVISIONED - After a transfer has completed, the provider state machine will transition to the deprovisioned state to clean up any remaining resources.

As with the contract negotiation state machine, custom code can react to transition events using the EventRouter. There are also two further options for executing operations during the provisioning step on the consumer or provider. First, a Provisioner extension can be used to perform a task. EDC also includes the HttpProviderProvisioner, which invokes a configured HTTP endpoint when a provider control plane enters the provisioning step. The endpoint can front code that performs a task and asynchronously invoke a callback on the control plane when it is finished.

Policy Monitor

It may be desirable to conduct ongoing policy checks for non-finite transfer processes. Streaming data is a typical example where such checks may be needed. If a stream is active for a long duration (such as manufacturing data feed), the provider may want to check if the consumer is still a partner in good standing or has maintained an industry certification. The EDC PolicyMonitor can be embedded in the control plane or run in a standalone runtime to periodically check consumer credentials.